On April 22, the world celebrated the fifty-fourth anniversary of Earth Day. Those in advertising and marketing might be interested to know that the sequence of events, ending up with Senator Gaylord Nelson inviting the nation to participate in Earth Day 1970, began with an ad by an iconoclastic San Francisco ad man named Howard Gossage.

An ad and an ad man? Yep. Here's the story:

Saving the Colorado River

In 1966, one of the first modern-day environmental activists, David Brower, was running the Sierra Club in San Francisco. At the time, the organization mixed environmental concerns with selling lovely books of national parks as photographed by Ansel Adams. And while public interest in the environment was growing, thanks to the widespread debate started by Rachel Carson’s renowned book on pesticides, Silent Spring, that interest remained concern, not action.

Brower and The Sierra Club had a problem: the Federal government had announced plans to flood the Grand Canyon (no kidding) by building a series of dams, essentially turning the roaring Colorado River into “dead water.” That seems outrageous today, but they were going to do it. In fact, they had already done it in Glen Canyon upstream from Grand Canyon National Park.

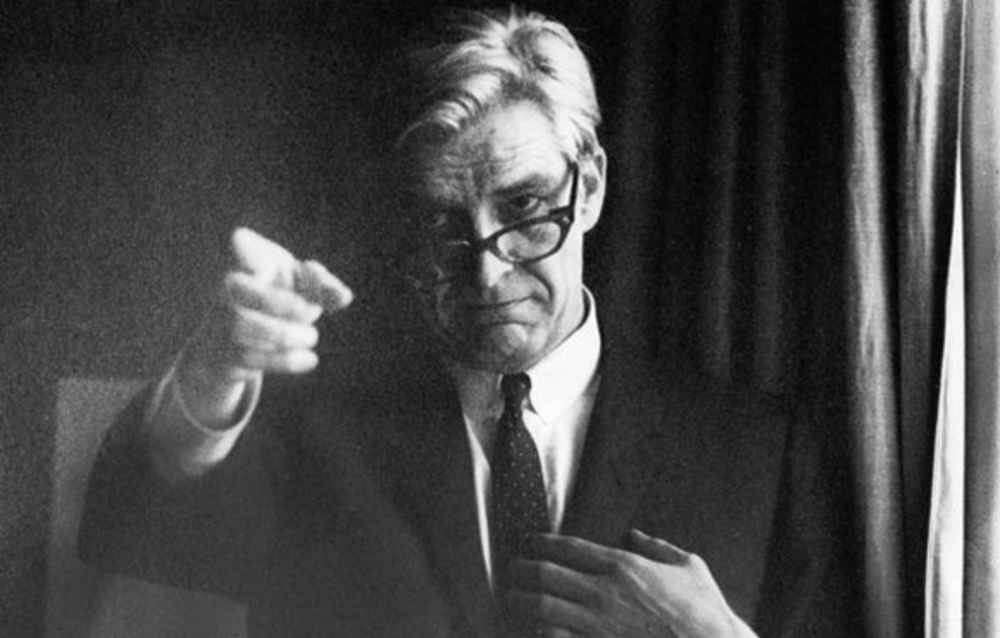

Fortunately, David Brower also had Howard Gossage, “The Socrates of San Francisco,” an outrageous advertising man running his revolutionary ad agency out of a renovated San Francisco fire house.

Gossage alternated between ads for clients like Irish Whiskey and Land Rover Motor Cars, and being a driving force behind things like Ramparts Magazine and the thinking of Marshall McLuhan.

Mr. Brower wanted to run an ad to stop the dams at Bridge Canyon and Marble Gorge. His idea was “An Open Letter to Stewart Udall,” then Secretary of the Interior.

Gossage thought otherwise. His point, recalled by then-partner Jerry Mander, was this.

“You can't just make people feel bad; you have to give them an opportunity to do something.” This thought was the beginning of modern media-driven activism.

The First Environmental Activism Campaign

As an alternative to Brower’s idea, Gossage’s agency created an ad headlined, “NOW ONLY YOU CAN SAVE GRAND CANYON FROM BEING FLOODED... FOR PROFIT.”

The ad included details about the House bill, the questionable science behind the project, and seven coupons. You could send them to the Secretary of the Interior, the President, your Congressman, both of your State Senators, and even the head of the Congressional Committee that was considering flooding the Grand Canyon for a dam. Or, you could donate to or join the Sierra Club.

The response was electric—coupons poured in, phones rang, newspapers ran stories and people got involved.

There was one additional response the very next day—from the Internal Revenue Service. They decided that since this ad was political lobbying, they were taking away the Sierra Club's tax-exempt status. Gossage thought that this was hilariously good news, amplifying the cause and leveraging the general dislike of the IRS. He was right.

Support for the Sierra Club grew; so did the publicity. The Canyon Dam bill was defeated the next week, having never reached the floor of Congress.

Meanwhile, Sierra Club membership doubled, from 39,000 to 78,000. It was a smashing victory, one that Brower remembered as a key moment in the nascent environmental movement.

A Movement Is Born

The media success and the “unseemly” publicity that went with it also caused a split between Brower and The Sierra Club… although they now look back at the incident with fondness, even celebrating the anniversary of the event.

At the time, they were not sure they really wanted all of this publicity and controversy. But David Brower was certain that this was exactly what he wanted. So was Howard Gossage.

In Brower's resignation speech to the Sierra Club, he announced the founding of a new organization. He then proceeded to walk down the street to his new offices—in Howard Gossage's Fire House.

As Brower friend and associate Tom Turner recalls, “We repaired to an office on the ground floor of an old firehouse in San Francisco, downstairs from ad man Howard Gossage, who had conspired with Dave to produce the newspaper ads largely credited with defeating two Grand Canyon dams… we settled on the name Friends of the Earth.”

Gossage continued to produce Sierra Club ads, campaigning to establish Redwoods National Forest. And when Senator Nelson announced Earth Day in 1969, the grassroots groundwork had already been prepared.

And that’s how and where the modern environmental movement began.

If not for Gossage's support—from initial communication inspiration to initial office space—the Grand Canyon might be flooded, and on April 22nd, we’d be celebrating Week After Tax Day.